Poking holes in reality with prototypes

Here's the text and images from my talk at Wuthering Bytes 2024. Credits / links are here. This isn't exactly what I said, I was distracted by a talking robot at one point for one thing 🤖

I had a really lovely time and met lots of interesting people. Thanks for asking me to speak Andrew.

I had a big fight with Wordpress over the formatting here and it still looks like crap boy Wordpress doesn't like align left.

Poking holes in reality with prototypes

Libby Miller, August 2024

I was midway through a PhD in the Philosophy of Economics in '96 or '97 with little to show for it except a solid loathing of Economics, a suspicion that its foundations as a subject were…how can I put it - bollocks…and - both a curse and a blessing - an ability to persist in something beyond all reasonable limits, so I was not giving up, but couldn't see a way forward either.

I was midway through a PhD in the Philosophy of Economics in '96 or '97 with little to show for it except a solid loathing of Economics, a suspicion that its foundations as a subject were…how can I put it - bollocks…and - both a curse and a blessing - an ability to persist in something beyond all reasonable limits, so I was not giving up, but couldn't see a way forward either.

And then, my housemate Dan Brickley, led me behind the curtain of HTML 'view source' and I was like: "oh: it's that easy!" "oh, maybe all programming is that easy" and then suddenly a boundary wall fell away and a whole new set of possibilities became apparent, for me.

Here's me a few years later 🤓

That conversation with Dan made a huge difference to my life and I love these moments and being part of them. I want to talk about how prototypes - shonky, modifiable, collaborative, silly prototypes - can provide these moments - can be tools for poking holes in reality, and how you design for this rather than it being a happy accident when you bumble into it.

In retrospect this is what I've been doing - or trying to do - for much of my career, and all because I was interested in what people really wanted from technology.

About me: After that conversation with Dan, I meandered my way into a tech career, worked in the Semantic Web at Bristol University at the fantastic ILRT, then in a long-forgotten peer-to-peer web TV startup, Joost; in March I left BBC R&D after nearly 15 years, where (by the end) I co-led a small multi-disciplinary team tasked with finding things the BBC could do in the future, with specific reference to young people, who basically don't use the BBC right now.

About me: After that conversation with Dan, I meandered my way into a tech career, worked in the Semantic Web at Bristol University at the fantastic ILRT, then in a long-forgotten peer-to-peer web TV startup, Joost; in March I left BBC R&D after nearly 15 years, where (by the end) I co-led a small multi-disciplinary team tasked with finding things the BBC could do in the future, with specific reference to young people, who basically don't use the BBC right now.

When I started at BBC R&D, with some honourable exceptions, interactions with 'users' were usually limited to the end of a project when prototypes were 'tested'. I found this extremely frustrating and highly illogical - how can you know what people want before you start? I wanted to find out more about what people wanted from technology before we started making things.

Our initial toe in the water was to make a basic picture of a radio on a postcard with stickers for buttons and dials - and we would go out and talk to people about what they wanted from it, and ask them to draw a picture of what the dials might do. The rubbish drawing of a radio avoided the problem of a blank page and helped people start to think about how radio technology featured in their lives and how they felt about it, and what would make it better. It was also novel, interactive, funny and something that they could understand and join in with. And very cheap compared with starting with technology.

The problem with this approach for radios, obvious in retrospect, but startling at the time for us, was that for younger people the physical radio didn't make any sense. Their radio was an app. And wasn't a radio. A picture of a physical radio didn't mean anything to them. A physical radio doesn't mean anything to them at all.

But drawings are a way into thingness

When I think about my laptop or phone, it's a cluttered mishmash of all the projects I have on the go, a bit like a messy room or a desk.

That clutter - which is made much worse browserification of everything - makes everything feel part of the same mishmash of undifferentiated stuff, flattened and made uninteresting by the screen. If you're thinking about something that's new, perhaps a new technology or feature for something and it just looks the same as everything else it's really hard to get people to make an imaginative leap into how it would feel for them to use that new thing, so you don't get authentic feedback.

Physical objects are much more interesting. Especially if you can embue them with the property of thingness (as my friend Richard Sewell calls it) - so that they embody one thing, a single idea.

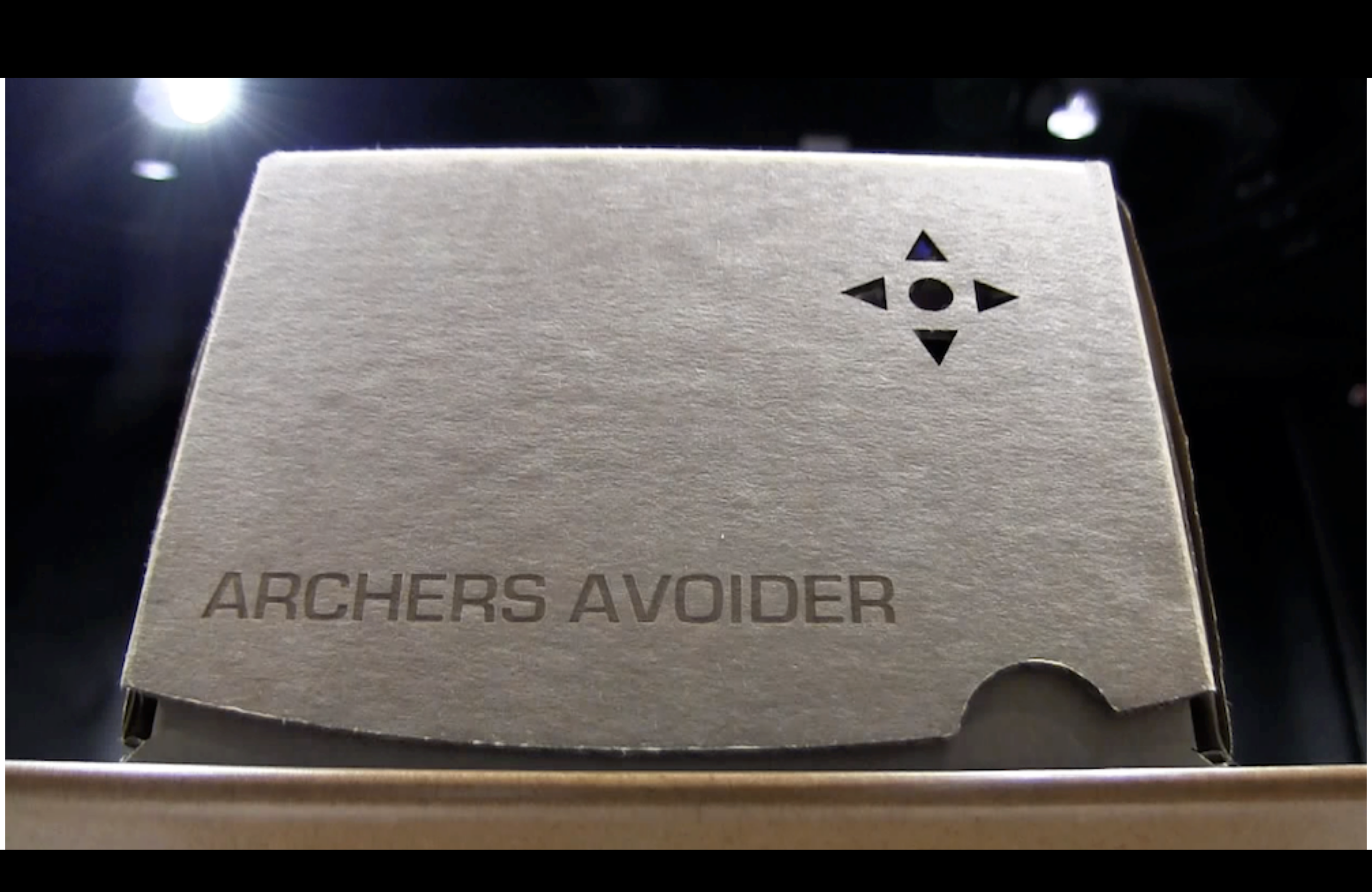

Here's an Archers Avoider. The Archers, as I'm sure you all know, is an extremely long-running audio soap opera on Radio 4. Many many people love the Archers. Many many people also hate it.

The Archers Avoider just does one thing - you press a button on the top and it avoids the Archers for you.

This enabled us to have a variety of interesting conversations about what you want to avoid on the radio, what stops you listening, what radio doesn't allow you to do, and what you do when other people just won't stop listening to the Archers when you are in the room.

Of course, if the BBC ever did make an Archers Avoider it would be a button on the app, but the physical embodiment of that button helped people engage with the idea.

'Engage' is a horrible piece of business speak

I think it means you are actually interested in something, but more than that, you might be able to imagine what it might be like to react and behave in that world bit of what it might be like to be in a world where that exists.

It did this because it was both silly and funny and single-minded.

For balance, here's an "Exclusively Archers" version that we also made, which switched itself on when the Archers came on and off again afterwards.

In R&D we made many of these kinds of things to gather information about how people felt about, say, talking TV guides or vague voice interfaces, randomising TV, mini games that help you choose what to watch, ambient, themed TV. And radio that helped you make music, or reacted to what you were doing or where you could choose your mood or a place where you could experience memories.

We designed a way to turn thingish objects into thingish applications, applications designed to express a single feature or idea, and then test those too.

But something was missing.

People could only respond to what we had made.

What about all the non-existent possible things in thingspace?

What I'm basically talking about here is technological futures.

The bit of thingspace we usually see is a tiny little sliver of the potential possibilities, projected by large corporations.

Here's one from Microsoft in 2015.

Corporate visions of the future often look like this kind of thing, smooth, seamless, integrated, shiny (things have got more boring lately because they are basically all just voice and AI interfaces).

Design fictions are more interesting than corporate visions of the future.

They are little puzzles that invite you to extrapolate from an image or an object, by making a little bit of reality from a possible future for you. And there can be lots of them, representing lots of glimpses into different futures.

These are some of the first ones I came across.

This image is of a robot repair shop by Strange Telemetry in 2015, which helps you weave a little story around how we ended up in a future with a family run robot repair shop, open 24 hours.

Or this, pretend packaging for the “Maidstone Saveloy” - a 100% cricket protein saveloy, with local protected geographical designation as part of a project on "time capsules from the future", made by Changeist and Smithery working with the Royal Society in 2017.

I love both of these and me and my friend Henry Cooke used to use them all the time in our "futures" work in R&D, particularly when we worked with students. But the robot workshop one is (as far as I know) the product of a designer or team, just like the corporate one.

To me the most interesting part of the second of these artefacts was how they were made by working early on with people to think about their future.

Smithery ran a workshop with a group of 13 year olds in order to come up with the saveloy and other ideas (you can read more on his website). So the saveloy wasn't just a product of a single designer's vision, or even a team in a company working together, but something much more interesting.

A short digression.

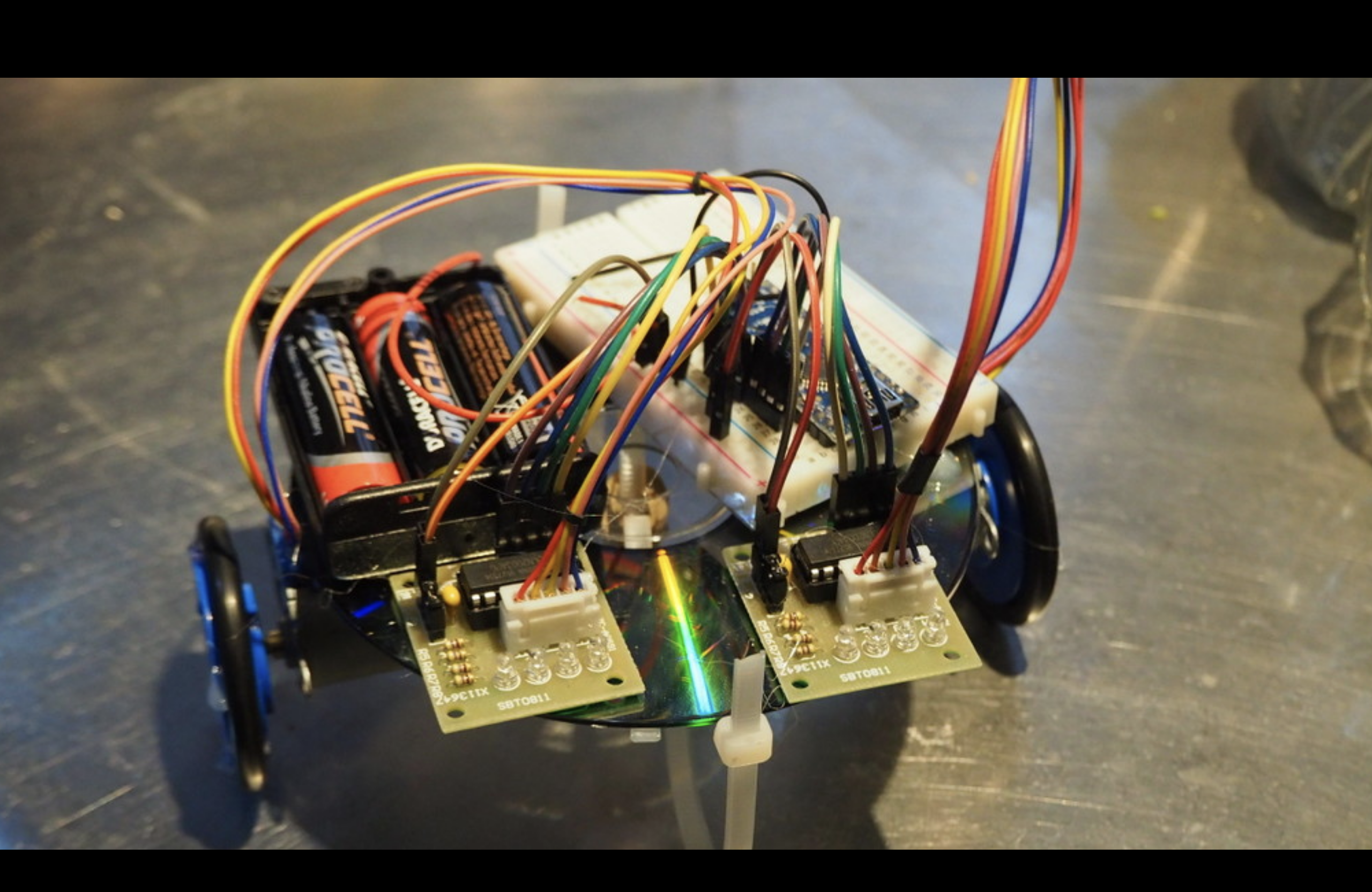

Meet…shonkbot

On a long drive back from Newcastle, my friends Richard, Anton and Matt came up with an idea: what would the cheapest moving robot look like? what could it do? and came up with Shonkbot. It's pretty shonky, as you can see.

Here's it doing its thing (writing its name). It can also avoid things.

Now when I was getting into electronics, soldering was a big hurdle for me. In fact, I didn't even know you had to solder boards until my now-friend John Honniball was kind enough to figure out what I wasn't doing.

I don't know if it was intentional or not but a side effect of the shonkbot approach was that no soldering was needed - so then immediately the whole thing was more accessible. In fact, you didn't need any tools at all, just some bits and bobs of electronics and a CD and a pen - and when we provided those bits, young kids and older adults and anyone in between (including R&D engineers and producers) could make themselves a robot.

Making a robot like this that provides a way in, and demystifies what a robot is. It means that in your world robots become something you can make, not things that happen to you or that you don't understand.

So shonkbot for me and many others demystified the technology. Only somewhat, but it was a way in. It shifted the walls enough to make electronics, robotics even! feel attainable.

And things that look a bit shonky or homemade or have pieces missing allow people to bring in their own ideas of what they could be, a bit like the drawings of radios, it's easy to join in, there's no smooth finished surface repelling your curiosity about what's in there and how it works and how you might change it

If you as a participant can join in and bring your own ideas then we can start to explore much more of the thingspace.

And for you as a participant, it's not just feeling what the future might be like, but getting a sense of what the technology can do, and that you can put your hands on it and change it so it makes sense for you. And feeling that you might actually want to do that, too.

The image is of a lovely example of home-made-ness - a wildlife camera by Interaction lab - mynaturewatch - a working, yet obviously home made wildlife camera. I use mine all the time.

For my final couple of projects at the BBC we worked on the collaborative aspect of exploring thingspace.

For my final couple of projects at the BBC we worked on the collaborative aspect of exploring thingspace.

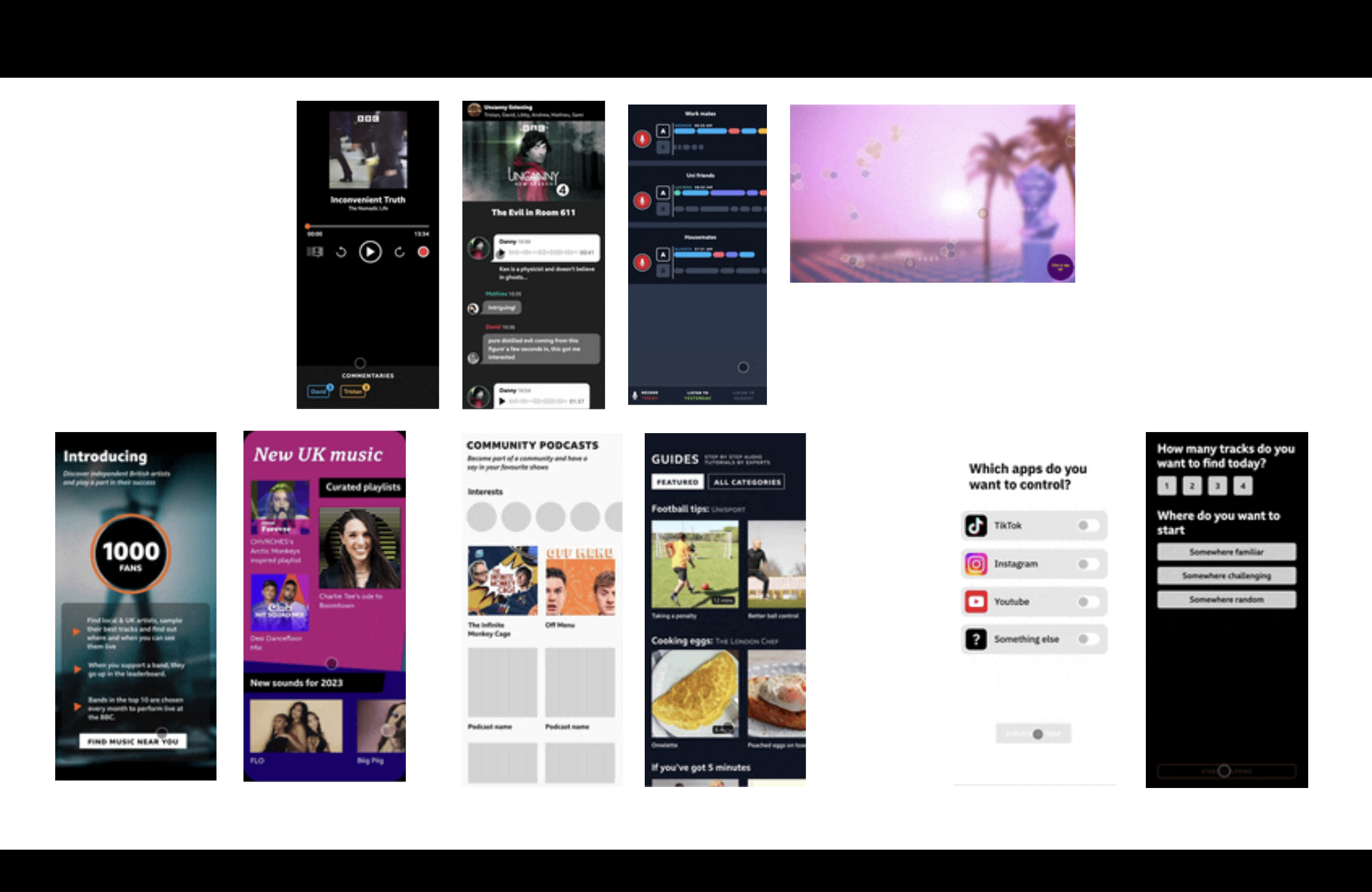

In this project designed by my friend Tristan Ferne, (which was about the BBC's incredible music resource, BBC Introducing, a place for new and emerging artists to get their work seen on the BBC), we spent a good deal of time experimenting to try and understand how best to collaborate with our target audience of 18-24 year olds.

In the end we had a really good process that treated them almost as clients. We interviewed them about their lives, showed them a wide range of possible thing-like prototypes based on those interviews, and then generated even more prototypes based on what they told us.

We asked them to imagine parts of the apps that didn't exist and gathered more information about their lives from those gaps.

What struck me most about that project was what it revealed about the 18-24s we spoke with: their "it is what it is" attitude. They were spending too much time on tiktok / insta but couldn't see a way to stop. They were lonely but couldn't see a way to connect with people. They were 'stuck' in algorithms that never showed them anything truly, genuinely new. They did not feel they could change things. And it was apps, specific apps that were their walls and formed the boundaries of their lives.

This reminded me very much of a writer my friend Tim Cowlishaw introduced me to the work of, Mark Fisher. He spends a book called "Capitalist Realism" expounding on the quote attributed to Žižek, "it is easier to imagine an end to the world than an end to capitalism" - because it pervades our lives so completely and so invisibly constrains our thoughts and actions.

These young people had a layer on top of that that constrained their thoughts and actions. They couldn't imagine the world without Instagram and Tiktok.

And that came from their very sophisticated understanding of the socio-economic-technical-design systems that make it so.

And it manifested as a sort of absence of drive and emotion towards the future.

It's clear that the big tech companies dominate how we think about the future using 'technological inevitability' arguments. Oddly enough, currently, they are all weirdly similar versions of the future: "your life now but with a bit less faff because of your internet butler"

At the same time, some of them are also feeding us reguritated slurry of generated un-novel "content".

We can have a sophisticated understanding of why and how this is happening without being able to feel as if there are real alternatives.

So, here's the final prototype I want to talk about.

My friend Jasmine Cox and I were tasked with designing a BBC 100th object - a thing from the future to go with 99 other BBC things on a website to commemorate 100 years of the BBC. We could have just made something up. We were R&D experts. And we did - we made this:

MZ Environmental Sampler from 2041 and a selection of interpretations of its data

The one in the BBC's collection was made by a year 4 class using the BBC micro:bit27. It reads and monitors the health of the system of fungi that connects plant roots together, the mycorrhizal network. As part of its services the BBC provides real-time reviews and forecasts from the UK's national open network of air, water and soil sensors.

It's a pretend prototype, not real, but based on as much natural science, physics and public service economics as we could muster.

But, inspired by Smithery's work, and working with our much-under-appreciated colleague Marvin McKenzie (who runs schools outreach at the BBC) - before we started thinking about what the 100th object could be, we worked with young children to try and understand their lives and the things they cared about, since that they were the people who would be experiencing that future world.

We gave them agency to be inventors by leading them through a version of our prototyping process.

We then used their ideas to invent something with them for the future.

It absolutely is possible to work with kids who are 8 or 9 years old in this way, by giving them tools and confidence, and part of that is by making home made objects that represent how they feel about their lives now and what they want from technology in the future.

So in a world where technology is eating its own content and regurgitating out the same stuff but more average.

I think we need lots of shonky, home made, thingish, funny, collaborative prototypes to give ourselves the imagination and agency to explore more of the possibilities and to gather the drive to change things.

Not corporate visions or design fictions which are a future a designer invented, but collaborations between technologists, designers, scientists, engineers and producers and the people who have to live with the things they make

- because we want more people to feel like they have, and ideally actually have some power over the future of this stuff

- or at least the capacity to have interesting opinions as a way to push back on the boring, frustrating sameiness of the big tech companies

- because that is also the path to a few of them making their own technology, becoming those people, and actually making alternatives

- and to give the producers, technologists, scientists and engineers the tools to challenge the status quo within their industries

- because without showing that there are real possible alternatives the status quo feels so implacably inevitable.

I want to thank Richard, Jasmine and Danbri for their comments on earlier versions of this talk

I am also keen to do more of this work so if you know of a way please tell me! I'm at @libbymiller@mastodon.me.uk