Prototyping and Power

This is my talk from the Pervasive Media Studio Lunchtime Talk on 24 Jan 2025. For more on the importance of shonky prototypes, here's my previous talk, "Poking Holes in Reality with prototyping".

Thanks to the PM studio and Lawottim for hosting me. There's a video version on Youtube here. Thanks to everyone who reviewed it for me.

This is a talk about a little bit of my own history, some of the really great projects I've worked on, a recommendation for certain type of approach to projects, and a call to action to consider a missing piece of the problem. It's very much my personal view. My ex-colleagues may percieve things differently!

Here's me nearly 30 years ago. Not Mr Happy. fed up with my PhD, disappointed in the whole subject. I had not found my tribe; phds are a lonely business and philosophy of economics was an outlier in Bristol's economics department, which was mostly about mathematical modelling, auction theory and markets.

By showing me 'view source' in html - something he did to multiple people, with similar effects - my housemate Dan Brickley sent me on a journey to confirmed geek.

I forged myelf a career in technology, taught myself how to program, worked on the Semantic Web at the wonderful ILRT with Dan at Bristol University, then in a long-forgotten peer-to-peer web TV startup ('Joost').

In March 2024 I left BBC R&D (IRFS and Audiences teams) after nearly 15 years, where by the end I co-led a small team tasked with finding things the BBC could do in the future, with specific reference to young people, who …basically don't use the BBC right now.

All this time later, through working in research, a startup and then more research, technology has served me very well, and yet - technology as something that now pervades everything we do has not served us well. In fact I find myself drawn away from technology and towards things that are real, physical and tangible, have no screens, and allow people to stop, think, and form their own ideas.

[Image from Buttystock "Burning crisp sandwich on a plate on a log" by mytalkingfist & moosecream]

One of the reasons I was interested in Economics to start with was that I was intrigued by the way new things get invented and made. It drew me to Economics, and yet it's not something Economics was (maybe is, I'm long out of that game) equipped to answer.

But I wanted to know, how did a new sandwich get invented?

Actually the closest shop to my office at the UOB was a shop where you could choose your sandwich fillings and combine them. Having tried a few different things, I "invented" one (stilton and walnut, better, no salad, salt and pepper) which I still regard as the optimal sandwich. There the amateur sandwich maker, me, could invent a sandwich with the help of the expert, covering a range of options with many possible combinations.

So that's one way.

And the "expert-amateur [sandwich] discovery problem" seems to me to be an extremely important one.

Because people are experts in themselves and their own lives and we - you - are experts in other things (combining sandwich fillings, Javascript, Raspberry Pi audio streaming, ESP32s, whatever it is). So we need to try and combine those areas of expertise if we are to make something useful to people.

Here's my philosophy of R&D.

If we think about the possible space of, let's say, lunchtime foods, then we should start in places we might not even have thought of (by asking the people who are experts in their own lives) and then burrowing around the space around those places using our expertise. So we'll find out about maybe an interesting new Thai-German crossover place that people are going to and then invent things like basil and chili pretzels or green curry schnitzel sandwiches on dark bread and then test these and end up somewhere hopefully (and testably) popular.

So we're interacting with the people who are experts in their own lives at least twice: once to find out what they are already doing, and once to test our ideas. with them. Actually we probably ought to do the testing bit multiple times. And our expertise comes in when we're burrowing around the new space we have found.

This is a version of the 'double diamond' or as we used to call it - three onions. Essentially you are being extremely expansive and thinking of as many ideas as you can, and then filtering the ideas back down to the best ones - repeatedly. The difference here is I'm saying more about where we start each onion.

Now, I've (fairly!) recently left BBC R&D so it's still weighing on my mind: what we did that was great, why it was great, and why, ultimately we didn't manage to change a thing.

When I joined BBC R&D, with a few honourable exceptions, there were few interactions with "end users" and if there were, they tended to be "user testing" at the end of a project.

This always baffled me. Don't you want to know if the thing you want is actually wanted?

Well actually, on reflection, no.

This is a case where - to be really honest - no-one wants to hear that what they have invented is not wanted.

Research projects are in some sense about power, authority and who decides what gets made, and this matters, because while the power structures are in place, favoured projects will continue, and crowd out more interesting, relevant and useful ones.

So this is a story about a struggle to place some structures in place that would defeat - or at least prove valiant opponents to - the existing power structures in the organisation. But what we thought we were doing was implementing something that was already happening - but doing it in a more effective way.

I was part of this attempt to solve the expert-amateur discovery problem in R&D: how do you give amateurs - perhaps your future users or some people who need something - the tools to contribute meaningfully to some technical enterprise?

Solving the expert-amateur discovery problem is important for any organisation that wants to remain relevant as technologies, tastes, opinions change over time. Not just for lunch.

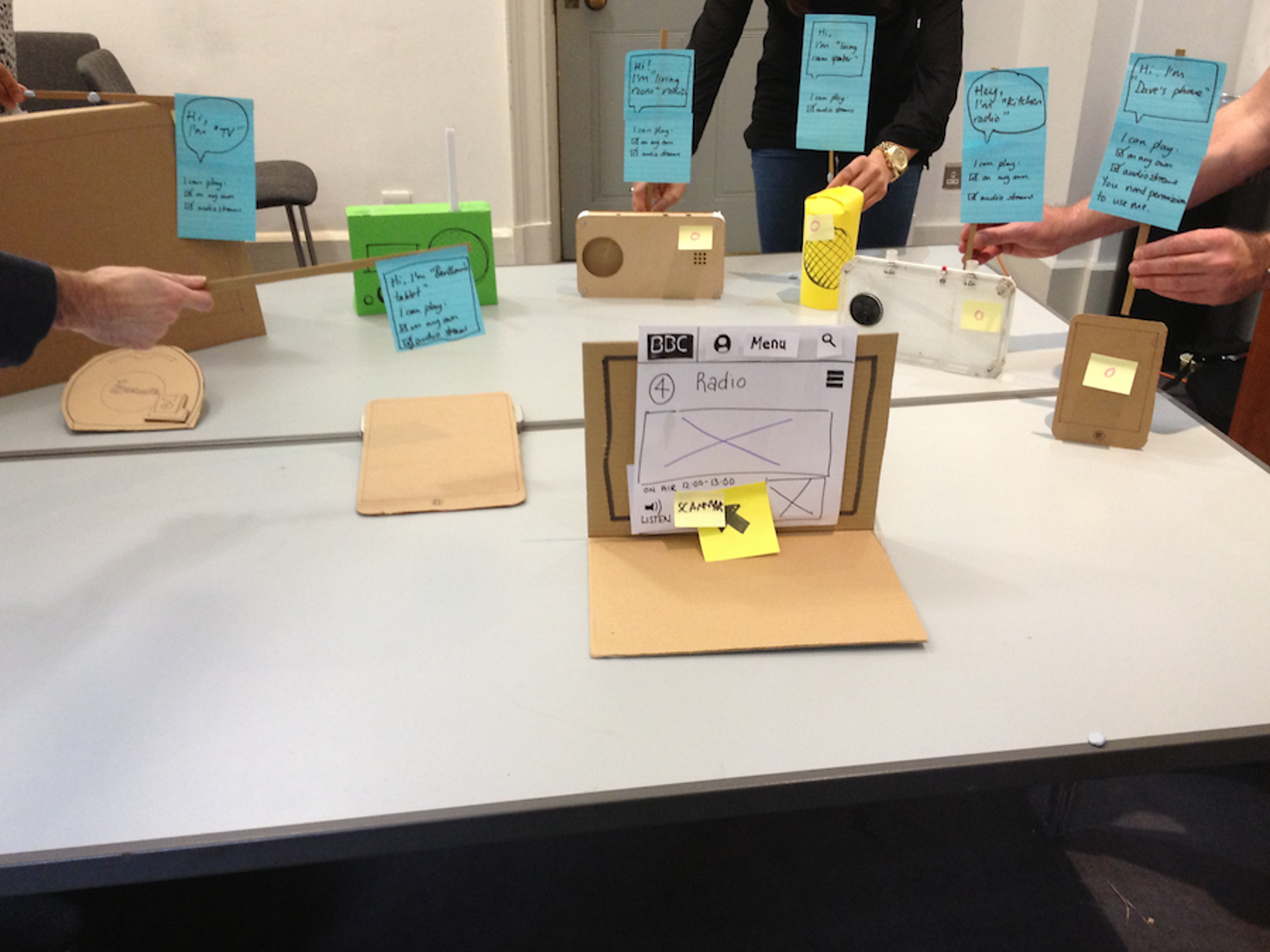

Here's an example of what I mean.

We dipped a toe in the water of understanding what people wanted by making these simple postcards - the project was about radio, we wondered what people wanted from a radio and this avoided the "blank page" problem - and most people could engage with a bit of drawing about their lives.

But one thing we discovered - obvious in retrospect but startling at the time - was that young people just didn't use physical radios. This little postcard process just didn't work for them because they didn't use them - if anything they were annoyed by their parents using them. So getting them to imagine what their ideal physical radio would do didn't work.

So this is an example of a technique which by its failure reveals that the whole sandwich ecosystem has been disrupted by, I dunno, the falafel upstarts. Lots of people are still buying sandwiches, but the falafel movement has revealed a major change in lunch habits.

Not sure how far I can take this analogy. But the point is, we woudn't have realised this without going out and asking humans about their lives in an inventive fashion, well before we started to actually prototype anything. Ultimately in this case it allowed us to broaden out our remit from sandwiches to lunch, or more non-metaphorically, from radio to the role of audio in peoples' lives, and respond to changes within society that we hadn't realised were there.

Why is it important?

- If you care about the quality and usefulness of the work you are doing, OR

- you care that your work improves the world OR

- you think it's important for fairness that people are involved in things that affect their lives OR

- you want to find something new in a crowded market

or some combination, then this is a good way of going about it. And we wanted to do all of these things.

People are experts in their own lives but you need ways to help them express what they think, want and need. Often people will be too shy, or just talk about things they have seen, or films or TV or something they heard on a podcast. You need to get them to reflect on their lives, and think, feel, and imagine the future.

One of our areas of expertise of our group in R&D was in designing techniques to help people do this. And many of them centred around prototypes.

[Image from "What do prototypes prototype?", Houde and Hill]

But perhaps not prototypes as you might be thinking of them.

I'm not talking about technology demonstrators or tests, or alpha websites.

I'm talking about things that elicit feelings and thinking from people about their lives, with respect to some technology.

The experimentation we did suggests that although something real-looking can help people imagine the role it would play in their lives, perhaps counter-intuitively, something unlike the real thing but which captures their imagination can be much more useful (and also, usually, cheaper)

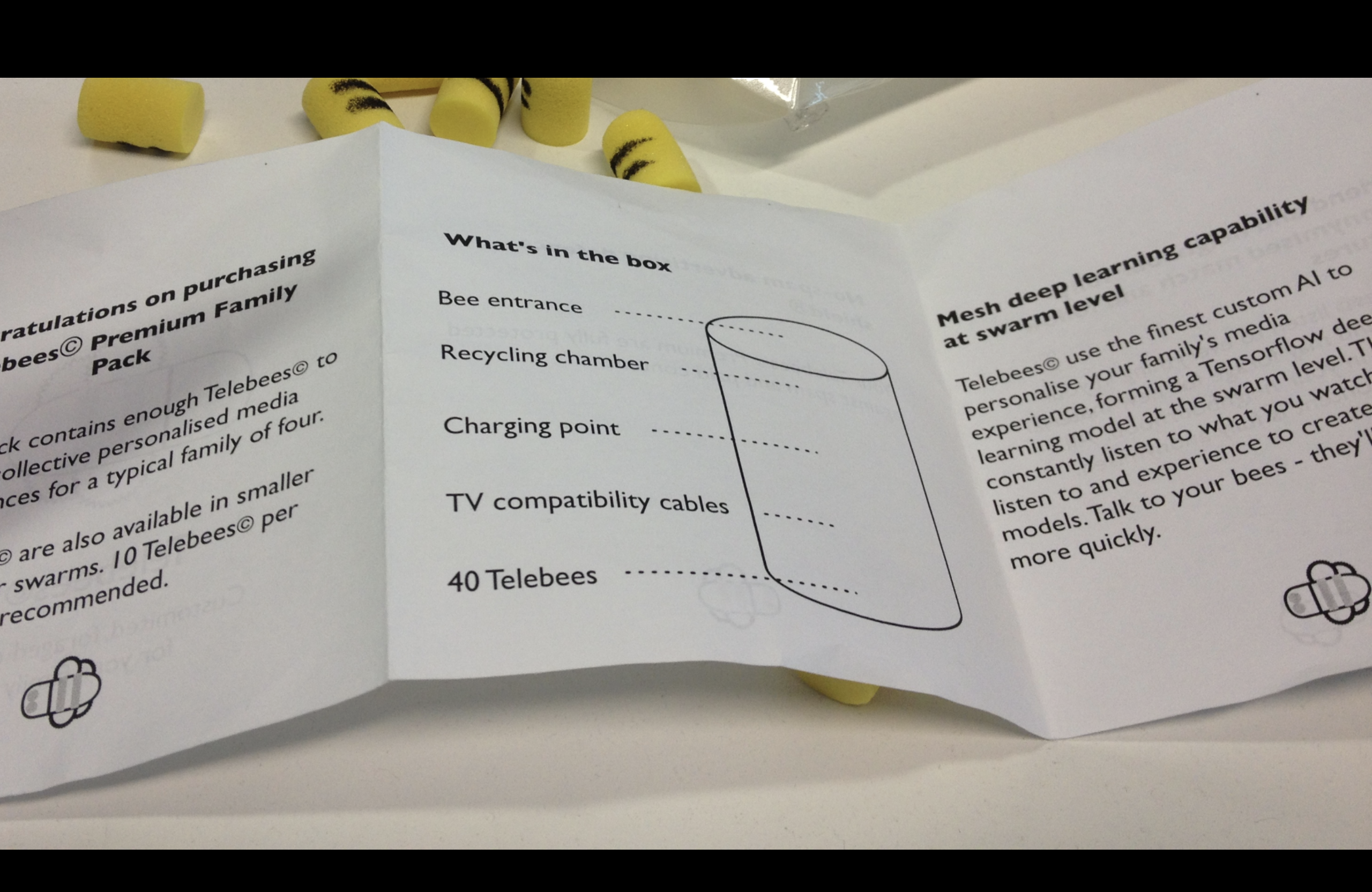

One technique we used draws on "thingness", (Richard Sewell's term) - if you can get people to interact with the right kind of thing - a physical thing ideally, and one which embodies one idea - then you can get great feedback and attention, authentic and genuine involvement in imagining what it would be like if this thing were real. And then you can apply those insights to digital objects or sandwiches or whatever you need to.

Here's an Archers Avoider. The Archers, as I'm sure you all know, is an extremely long-running audio soap opera on Radio 4. Many many people love the Archers. Many many people also hate it.

The Archers Avoider just does one thing - you press a button on the top and it avoids the Archers for you.

This enabled us to have a variety of enlightening conversations about what you want to avoid on the radio, what stops you listening, what radio doesn't allow you to do, and what you do when other people just won't stop listening to the Archers when you are in the room.

Of course, if the BBC ever did make an Archers Avoider (which obviously it never would) it would be a button on the app, but the physical embodiment of that button helped people imagine what it might be like to react and behave in that world It did this because it was both silly and funny and single-minded.

For balance, here's an "Exclusively Archers" version that we also made, which switched itself on when the Archers came on and off again afterwards. also just does one (opposite) thing too.

Physicality and thingness get you a long way in getting over the expert-amateur barrier. Physical objects avoid the flattening, boringness of screens and also the distractableness of phones and laptops - and so can persuade people to give you their attention and imagination.

You'll also notice quite a few of these things are also quite silly.

Thingness - singluarity of purpose - helps with testability by decomposing the problem.

Physical things summon peoples' imagination and attention

But humour and silliness defuse one of the most significant problems in this relationship - power.

In a corporate environment it's not really the done thing to do silly or funny things - and yet, it's the best way to give yourself and others permission to say what isn't being said. Plus it's (obviously) a lot more fun.

And when it comes to working with people where there's a big power differential, it lets them know that you are not intransigent and you don't know everything.

And here we come to one of my favourite projects - and one that proves that the expert-amateur power differential can be overcome even when it's huge. My friend Jasmine Cox and the talented Marvin McKenzie worked with 8 and 9 year olds to invent a thing for the future. We had to get past our "boffin" status and make sure that the kids understood that their ideas were valuable - while trying to understand their lives and not just have them talk about Wall-E or something they had done in class.

Silly and funny is a lot easier with kids of course.

But power differentials appear within the "expert" realm too and silliness can work there too.

After I moaned about the inability of R&D to stop projects, Richard and I made catwigs (github), a tool to critique a project - in a funny way - in several dimensions.

Here, humour is used as a power-reset button within a group working on a project, allowing people to speak out where they might not,

This was quite a powerful lesson for me, that turn-taking and explict rules for speaking can help enormously when people are hesitant to speak up, often those with actual hands-on knowledge of a project, and especially if they are young, shy and geeky, or have not been listened to before.

And it leads to all sorts of questions about projects

- who decides when to start and stop them?

- is anyone going to give up their power?

For any of these techniques to be effective, you've got to want to know more and accept that you don't know everything, that being great with say, node.js or immersive video or finance or management doesn't make you an expert on what these particular young people want from TV, for example.

And what about the "burrowing" part, the part where the experts take the new position in thingspace and think of things to make inspired by it? In some ways this is the exciting part, and the most fun part. We've done it collaboratively with potential end users, but also created various techniques to explore as much of that space as possible.

Analogies are great for this ("what if TV was a dog? milk?" [another Richard Sewell special]) and processes and tools that take examples from the physical world and then use that to think about the problem ("what is it about IKEA that makes discovery of new things interesting?") [from a hopefully forthcoming article by Mathieu Triay and Andrew Wood].

Physicality comes in here too. Acting things out is a brilliant way of imaginatively placing yourself in a situation where you might use something. Even imagining examples from the physical world can help.

[I didn't mention this in my talk but there are lots of existing techniques for this sort of thing - the term to look for is "design thinking"]

But the key thing is not to flatten or ignore or fail to develop ideas before they have had some space to flourish and effloresce. And this means - as with the catwigs example - giving all individuals space to speak and experiment. It also means that diverse, differently skilled, teams with different life experiences enable you to cover more of that potential space (there's plenty of evidence (archive) for this too).

Using these prototyping principles (and many custom techniques that we invented) in various combinations, we made some lovely things that people wanted. For example:

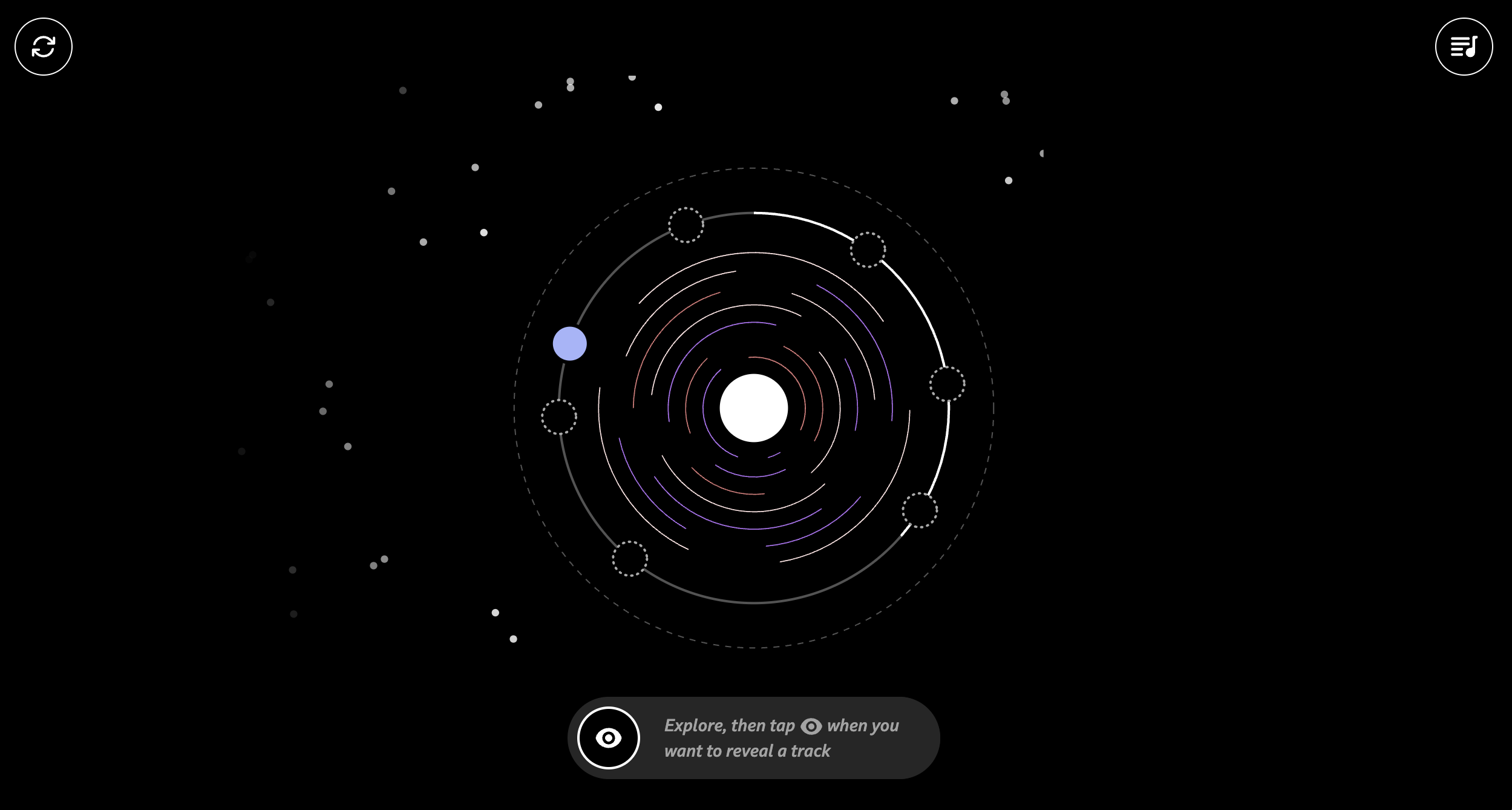

Orbit music a music browser purely about discovery, that helps you find genuinely new things to listen to in a beautiful and enjoyable way.

I didn't make this - it was mostly down to the brilliant Mathieu Triay - but I helped with the research. This was a project designed by my friend Tristan Ferne. It was about the BBC's incredible music resource, BBC Introducing, a place for new and emerging artists to get their work heard on the BBC.

We spent a good deal of time experimenting to try and understand how best to collaborate with our target audience of 18-24s. In the end we had a really good process that treated them almost as clients. We interviewed them about their lives, showed them a wide range of possible thing-like prototypes based on those interviews, and then generated even more prototypes based on what they told us.

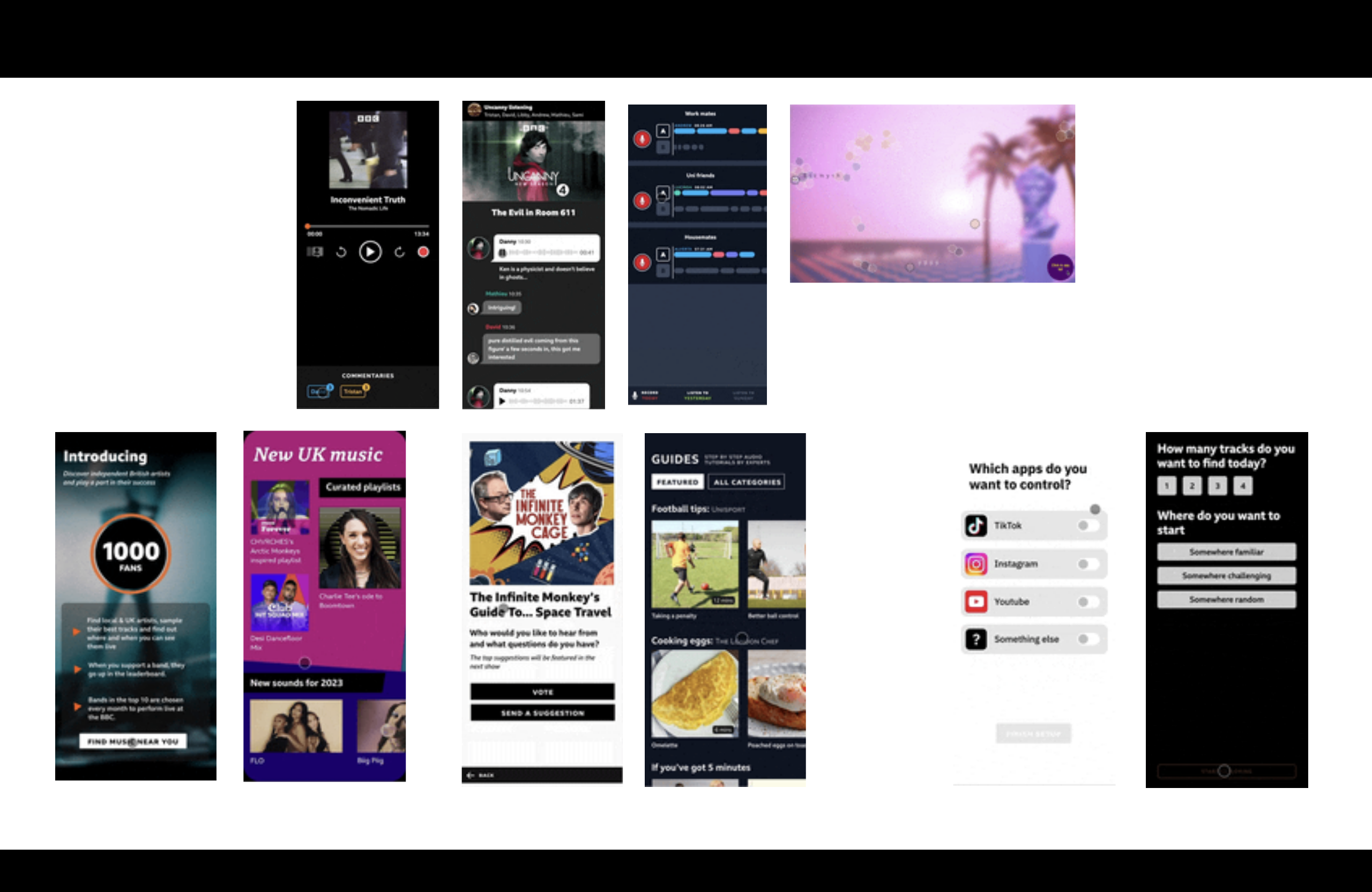

The second project I want to talk about is Tellybox - in the end we made four ways to help you make the best of the time you have to watch something with someone.

This project started with user research about what was difficult about watching TV, which turned out to be choosing what to watch. TV watching is a low stress, low effort way of hanging out with others, but this is completely ruined if you spend the first 30 mins of a limited time arguing about what to watch or scrolling through a TV app, getting more and more bored, irritated and despondent [it me].

We made and tested drawings, some very silly design fictions, nine working phyiscal prototypes, and then figured out a way to turn them into four digital objects which we could also test. The results included:

- a game where one player chooses five programmes, the next two, and the next one - and then you are all / both invested in whatever you both choose

- a randomiser that picks for you

- something that allows you to select programmes that fit the time you have (this would be trivially easy to implement, at least from a data point of view!)

- a voice based app that allowed you to vaguely select a kind of programme to watch, for vibe-based watching

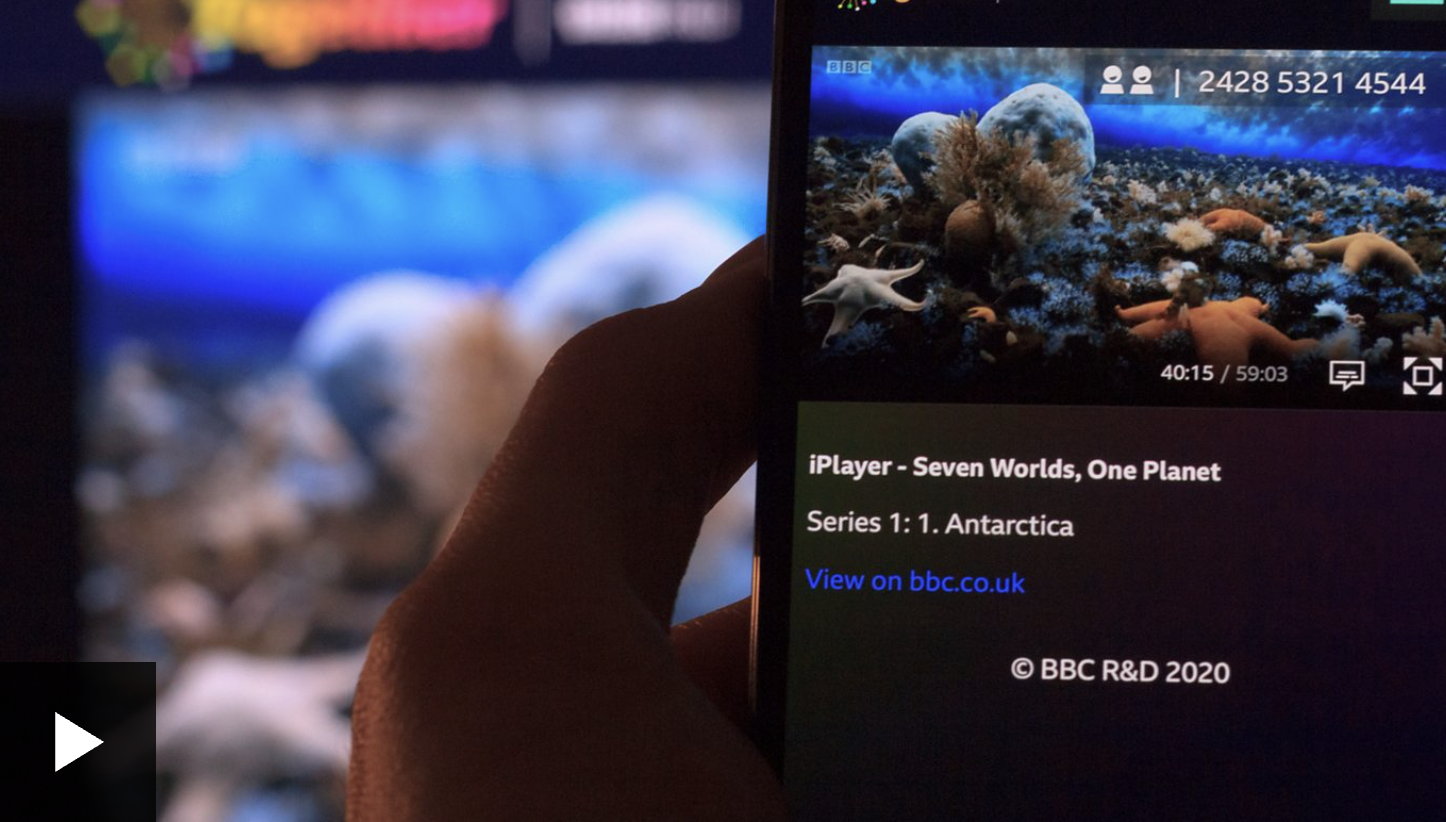

The final project I want to talk about is BBC Together - which was less thing-like and physical object based, because it was made during Covid. Like a lot of people at the time, we wanted to make something that would help, and we already had the synchronisation technology.

So we built a way to watch TV with loved ones at precisely the same time when you are apart from them. And here's a lesson I learned from this about evaluation and testing that's also a clue about power:

You can't do what people want you to do.

You can't show that you have the ideas, best structure, the best techniques, by getting large numbers of people using it, or by getting great qualitative feedback, because the counterfactual is what exists already - which at the BBC, already has more people using it than you could possibly have for a prototype.

BBC Together had many thousands of users and very high ratings. But that wasn't enough to change peoples' minds.

So blah blah yes Libby is great at this stuff, sees things differently, is very employable and so on. And, yes, yes I am. But

The structures and norms we put in place around listening to potential end users, getting them to imagine futures, working in multidisciplinary teams, listening to our colleagues, speaking truth to power, making all this part of projects, showing everyone the results over and over - long term, didn't even change R&D, never mind the BBC.

And that's where it all falls down of course 😩

Musing on this, as one does after nearly 15 years trying and failing to do something, I recently came upon a rather brilliant page of books that should exist but don't. And this specific one chimed with me -

"This book is for people who have been managing research projects long enough to become frustrated and furious by institutional inefficiency, inertia, and hypocrisy. Drawing on more than a century of community organizing, it explains how to figure out where power actually resides, how to build support for change, how to get into a position to make those changes…this book focuses on the practical "how" of being the right person in the right room on the right day to make things better a little bit at a time."

That seems like a very good expression of the remaining part of the problem. Flogging my analogy to death, we know how to find out how lunching is evolving, and we know how to invent different kinds of lunches, and both of those are really valuable to lunch-providing - or even any sustinance-providing organsations, if they are willing to listen. But what we don't know - never knew because we took people at face value when they said they were amenable to change - is how to get them to listen and then act.

We were trying to build new ruts, a new culture - but it didn't take, perhaps because we thought that it would be obvious how great the techniques were by the cool things we came up with. And in R&D you expect to fail, multiple times (but not all the time).

Mathieu made a very interesting point while critiquing these slides for me: in fact people did, eventually listen to us - but they didn't - or couldn't - act on the recommendations we gave them, even when we presented them with existential threats to the organisation. It was just too difficult for them to do so. Inertia, conservatism (small c) and technical debt were all reasons not to act.

"It's easier to drop it…until time and external forces have eroded enough of a path that there isn't a choice left and everyone falls all at once in the new ravine"

I'm interested in how we might accelerate this falling into the ravine - I think this quote from Cory Dotorow is probably key -

"Any time you see a group of people who've tried over some long timescale to do something, without success, it's *possible* that their failure is down to having bad tactics, but it's *far* more likely that they've failed because they just aren't powerful enough on their own to save the owls, or the planet, or their would-be ethnostate or whatever they're agitating for."

Change comes from coalitions of groups with the same interest, so if we think we have some great, successful, fair ways of working, then we need to build coalitions to make them the new norms, the new ruts, the new ravine.

This is important because these techniques and attitudes can - if actually acted upon - lead us to technologies that are closer to what people actually want and need.

What I'd love to know from you:

- have you tried techniques like this?

- have you succeeded?

- how did you know you had succeeded?

- Have you changed institutional minds? how??

I'm off to build some coalitions I think!

I'm very interested in any thoughts and questions you have.